In finance, a futures contract (often referred to simply as futures) is a standardized legal agreement to purchase or sell an asset at a set price, with delivery occurring at a predetermined future date, between parties who do not yet know each other. This asset is typically either a commodity or a financial instrument. The agreed-upon price in the contract is called the forward price or delivery price. The future date when delivery and payment are to take place is known as the delivery date. As a financial instrument that derives its value from an underlying asset, a futures contract is classified as a derivative.

Contracts are exchanged at futures exchanges, which serve as a marketplace connecting buyers and sellers. The individual purchasing a contract is referred to as the long position holder, while the individual selling is known as the short position holder. To mitigate the risk of either party defaulting if the market price moves unfavorably, both parties might be required to deposit a margin, which is a portion of the contract’s value, with a trusted third party. For instance, in the trading of gold futures, the margin requirement typically ranges from 2% to 20%, depending on the volatility of the spot market.

A stock future is a cash-settled futures contract based on the value of a specific stock market index. Stock futures represent one of the higher-risk trading instruments available. Additionally, stock market index futures are utilized as indicators to gauge market sentiment.

A stock future is a cash-settled futures contract based on the value of a specific stock market index. Stock futures represent one of the higher-risk trading instruments available. Additionally, stock market index futures are utilized as indicators to gauge market sentiment.

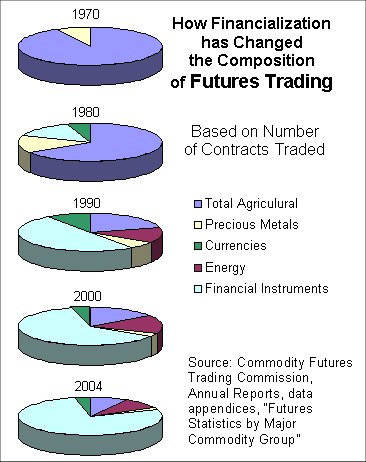

Initially, futures contracts were negotiated for agricultural commodities, followed by contracts for natural resources like oil. Financial futures emerged in 1972, and in recent years, futures for currencies, interest rates, stock market indices, as well as cryptocurrency inverse futures and perpetual futures, have become increasingly significant in the futures markets. There have even been proposals for organ futures to enhance the availability of transplant organs.

The primary purpose of futures contracts is to reduce the risk associated with price or exchange rate fluctuations by enabling parties to lock in prices or rates for future transactions. This can be particularly useful when, for instance, a party anticipates receiving payment in a foreign currency at a later date and wants to protect against potential adverse movements in the currency value before the payment is made.

However, futures contracts also provide opportunities for speculation. A trader who anticipates a price movement in a specific direction can enter into a contract to buy or sell the asset at a future date. If their prediction proves accurate, they can make a profit. Specifically, if the speculator benefits from their trade, the underlying commodity would have been stored during periods of surplus and sold during times of scarcity, thereby offering consumers a more advantageous distribution of the commodity over time.

Origin

The Dōjima Rice Exchange, founded in Osaka in 1697, is often regarded as the earliest futures exchange market. It was established to address the needs of samurai who, being compensated in rice, required a stable conversion to coin following a series of poor harvests.

In 1864, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) introduced the first standardized ‘exchange traded’ forward contracts, known as futures contracts. These contracts were based on grain trading and set a precedent for creating contracts for various commodities and establishing futures exchanges globally. By 1875, cotton futures were being traded in Bombay, India, and soon after, futures were introduced for edible oilseeds, raw jute, jute products, and bullion. In the 1930s, wheat futures accounted for two-thirds of all futures trading.

The establishment of the International Monetary Market (IMM) by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in 1972 marked the inception of financial futures exchanges and the launch of currency futures. The IMM expanded in 1976 by introducing interest rate futures on US Treasury bills, and by 1982, it had added stock market index futures.

Risk mitigation

Although futures contracts are designed for a future date, their primary function is to manage the risk of default by either party during the interim period. To this end, the futures exchange requires both parties to deposit an initial amount of cash, or a performance bond, known as the margin. Margins, often expressed as a percentage of the futures contract’s value, must be maintained throughout the contract’s duration to ensure the agreement is upheld. This is because the contract’s price can fluctuate based on supply and demand, leading to potential losses for one side and gains for the other.

To manage default risk, the contract is marked to market daily, meaning the difference between the initial agreed-upon price and the current daily futures price is recalculated each day. This process, referred to as the variation margin, involves transferring funds from the losing party’s margin account to the winning party’s account, reflecting the daily profit or loss accurately. If a margin account falls below a certain threshold set by the exchange, a margin call is issued, requiring the account owner to top up the margin.

On the delivery date, the amount exchanged is based on the spot value rather than the contract’s specified price, as any gains or losses have already been settled through the daily marking to market process.

Margin

To reduce counterparty risk for traders, trades executed on regulated futures exchanges are guaranteed by a clearing house. The clearing house effectively acts as the buyer to each seller and the seller to each buyer, thus assuming the risk of loss in the event of a counterparty default. This system allows traders to execute transactions without needing to perform due diligence on their counterparties.

In some cases, margin requirements may be waived or reduced for hedgers who physically own the covered commodity or for spread traders who hold offsetting contracts that balance their positions.

Clearing margins serve as financial safeguards to ensure that firms fulfill their obligations on open futures and options contracts with customers. These clearing margins are distinct from customer margins, which are the funds individual buyers and sellers of futures and options contracts must deposit with brokers.

Customer margin refers to the financial guarantees required from both buyers and sellers of futures contracts and sellers of options contracts to ensure contract fulfillment. Futures Commission Merchants oversee customer margin accounts, with margins determined based on market risk and contract value. This margin is also known as performance bond margin.

Initial margin is the equity required to open a futures position, acting as a performance bond. The maximum exposure is not confined to the initial margin amount, but the initial margin is calculated based on the maximum expected change in contract value within a trading day. The exchange sets the initial margin requirements.

For exchange-traded products, the initial margin amount or percentage is determined by the relevant exchange.

If the value of a position declines or the initial margin is depleted, the broker will issue a margin call to restore the margin account to the required level. This process, often referred to as “variation margin,” typically occurs daily but can be intraday during periods of high volatility.

Margin calls are generally expected to be settled on the same day. If not, the broker has the authority to close enough positions to cover the margin call, with the client being liable for any resulting shortfall in their account.

Some U.S. exchanges use the term “maintenance margin” to define the minimum margin level that must be maintained before a margin call is issued. Most non-U.S. brokers, however, use only “initial margin” and “variation margin.”

The Initial Margin requirement is set by the futures exchange, unlike other securities’ Initial Margin, which is established by the Federal Reserve in the U.S. markets.

A futures account is marked to market daily. If the margin falls below the maintenance margin level set by the exchange, a margin call will be issued to restore the account to the required level.

Maintenance margin is the minimum margin per outstanding futures contract that a customer must maintain in their margin account.

The margin-equity ratio is a term used by speculators to represent the proportion of their trading capital held as margin at any given time. Due to the low margin requirements of futures, investments are highly leveraged. Exchanges set a minimum margin requirement, which may vary by contract and trader. Brokers may set a higher requirement but cannot set it lower. Traders can choose to set their margin above the minimum to avoid margin calls.

Performance bond margin is the amount deposited by both a buyer and seller of a futures contract or an options seller to ensure contract performance. Margin in commodities is not an equity payment or down payment on the commodity itself but rather a security deposit.

Return on margin (ROM) is often used to assess performance, representing the gain or loss relative to the exchange’s perceived risk as reflected in the margin requirement. ROM can be calculated as (realized return) / (initial margin). The annualized ROM is (ROM + 1)^(year / trade_duration) – 1. For example, a 10% gain on margin over two months would be approximately 77% annualized.

Settlement − physical versus cash-settled futures

Settlement refers to the final execution of the contract and can occur in two ways, depending on the contract type:

- Physical delivery involves the seller delivering the specified amount of the underlying asset to the exchange, which then transfers it to the buyer. This method is common with commodities and bonds but occurs infrequently as most contracts are canceled by purchasing a covering position. Most energy contracts on the NYMEX use physical delivery. Many contracts are settled by closing positions or through an Exchange For Physical (EFP) arrangement. Some Treasuries contracts on the CBOT also use physical delivery.

- Cash settlement involves a cash payment based on an underlying reference rate, such as a short-term interest rate index or the closing value of a stock market index. Parties settle by paying or receiving the cash equivalent of the contract’s gain or loss at expiration. Cash-settled futures are used when physical delivery is impractical, such as with indices. ICE Brent futures use this method.

Expiry (or Expiration in the U.S.) is the date when a particular delivery month of a futures contract ceases trading and the final settlement price is determined. For many equity index futures, interest rate futures, and equity (index) options, expiry occurs on the third Friday of certain months. On this day, the back month futures contract becomes the front-month contract. For example, after the December contract expires, the March futures become the nearest contract. During this period, futures and underlying asset prices may temporarily diverge, with increased trading volume as traders roll over positions or hedge against index positions. Exchanges enforce strict limits on exposure near expiration to prevent volatility.

Pricing

In situations where the underlying asset for a futures contract is abundantly available or can be easily produced, the contract’s price is established through the mechanism of arbitrage. This is common for futures on stock indices, government bonds, and physical goods such as agricultural products during periods of availability post-harvest. On the other hand, if the asset that can be delivered is scarce or does not yet exist—like crops before they are harvested or in the case of Eurodollar and Federal funds rate futures, where the underlying instrument is to be generated at the time of delivery—the arbitrage method cannot be used to set the price. In such cases, the sole determinant of the futures price is the market’s supply and demand for the asset at a future date, reflected by the trading dynamics of the futures contract itself.

Arbitrage arguments

The concept of arbitrage rationale, often referred to as “sensible pricing,” is relevant when the asset that can be delivered is widely available or can be easily produced. In such cases, the forward price is considered the anticipated future value of the asset in question, adjusted by the risk-free interest rate. Any discrepancy from this theoretical price presents an opportunity for investors to earn a profit without risk, which is typically eliminated through arbitrage. The forward price is determined as the strike price K, ensuring that the contract holds no value at inception. With the assumption of a stable interest rate, the forward price for a futures contract is equivalent to that of a forward contract with identical terms. This equivalence holds true even if the underlying asset’s value does not correlate with interest rates. However, if there is a correlation, the variance in the forward price of the futures (the futures price) compared to the forward price of the asset is directly related to the covariance of the asset’s price and the interest rates. For instance, the futures price of a zero-coupon bond is typically lower than its forward price, an adjustment known as the “convexity correction” in futures pricing.

In the context of a stable interest rate environment, the calculation of the futures or forward price for a non-dividend yielding asset is achieved by increasing the spot price at time ‘t’ to the future time ‘T’ using the risk-free interest rate ‘r’.

The formula for this calculation is given by:

[ F(t,T) = S(t) \times (1 + r)^{(T – t)} ]

or, when using continuous compounding, it can be expressed as:

[ F(t,T) = S(t) \times e^{r(T – t)} ]

This formula can be adjusted to account for additional factors such as storage costs ‘u’, dividend yields ‘q’, and convenience yields ‘y’. Storage costs represent the expenses incurred in holding a commodity for future sale at the futures price. When investors sell the asset at the spot price to exploit a discrepancy in the futures price, they effectively earn the storage costs they would have incurred had they held the asset.

Convenience yields, on the other hand, are the non-cash benefits of holding an asset for future sale, such as the capacity to fulfill sudden demand or to utilize the asset in production processes. Investors forgo these benefits when they sell at the spot price, and this is reflected in the formula as a loss of convenience yield.

The adjusted formula incorporating these elements is:

[ F(t,T) = S(t) \times e^{(r + u – y)(T – t)} ]

The convenience yield ‘y’ is not directly observable and is often derived from the additional yield that investors receive when they sell at the spot price to exploit the futures price, given known values of ‘r’ and ‘u’.

Dividend or income yields ‘q’ are more straightforward to observe or estimate and can be integrated into the formula in a similar manner:

[ F(t,T) = S(t) \times e^{(r + u – q)(T – t)} ]

In an ideal market, the relationship between futures and spot prices is solely determined by these variables. However, real-world market imperfections such as transaction costs, varying borrowing and lending rates, and limitations on short selling can impede perfect arbitrage. As a result, the actual futures price oscillates within a range defined by these theoretical boundaries.

Pircing via expectation

In scenarios where the commodity to be delivered is scarce or not yet in existence, the concept of rational pricing does not hold sway, given that the arbitrage process is inapplicable. In such cases, the pricing of futures contracts is shaped by the current market’s supply and demand dynamics for the asset at a future point in time.

Within a well-functioning market, it is anticipated that supply and demand will align at a futures price that corresponds to the present value of an impartial forecast of the asset’s price on the delivery date. Mathematically, this can be articulated as:

[ F(t) = E_t{S(T)}e^{(r)(T-t)} ]

However, in markets that are not deep or are illiquid, or in instances where a significant portion of the deliverable commodity has been intentionally removed from the market’s reach (an unethical practice known as market cornering), the price that clears the market for futures may still reflect the equilibrium of supply and demand. Nonetheless, the connection between this market-clearing price and the anticipated future value of the asset may become disrupted.

Arbitrage and Anticipated Pricing Dynamics

In an environment where arbitrage opportunities are minimized, the anticipated pricing of assets hinges on the assumption of a risk-neutral valuation framework. Essentially, this means that the price of a futures contract should mirror a fair assessment of the underlying asset’s future value, adjusted for the time value of money under a risk-free rate scenario. This equilibrium ensures that traders, on average, do not anticipate gaining an advantage from market inefficiencies.

Market Structures: Contango, Backwardation, and Market Orientations

When the cost of a commodity scheduled for future delivery exceeds its anticipated market value, this scenario is characterized as contango. This typically occurs in a market structure where the present value of the commodity is less than the prices of futures contracts, with the further-out contracts commanding higher prices than those closer to expiration. Conversely, backwardation is observed when the future delivery cost of a commodity is less than its expected market value, often seen in a market where current prices are higher than futures prices, and the prices of distant-dated contracts are lower than those of near-dated ones. This reflects an inverted market structure, where the temporal sequence of prices is reversed compared to the normal or contango situation.

Futures contracts and exchanges

Contracts

Futures contracts come in various forms, reflecting the diversity of “tradable” assets they can be based on, including commodities, securities (such as single-stock futures), currencies, and intangibles like interest rates and indexes. For details on futures markets in specific underlying commodity sectors, follow the provided links. A list of traded commodities futures contracts can be found in the List of traded commodities. Additionally, see the futures exchange article for more information.

- Foreign Exchange Market – Refer to Currency Futures

- Money Market – See Interest Rate Futures

- Bond Market – Refer to Interest Rate Futures

- Equity Market – Consult Stock Market Index Futures and Single-Stock Futures

- Commodity Market

- Cryptocurrencies – Check Perpetual Futures

Futures trading has historical roots dating back to 18th century Japan with rice and silk, and in Holland with tulip bulbs. In the US, futures trading began in the mid-19th century with the establishment of central grain markets, creating a platform for farmers to sell their commodities either for immediate delivery (spot or cash market) or for future delivery. These initial forward contracts between buyers and sellers evolved into today’s exchange-traded futures contracts. While early futures trading focused on traditional commodities like grains, meats, and livestock, it has since expanded to include metals, energy, currencies, equity indexes, government interest rates, and private interest rates.

Exchanges

In the 1970s, financial instruments futures were introduced by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), rapidly gaining popularity and surpassing commodity futures in trading volume and global market access. This development led to the creation of numerous futures exchanges worldwide, including the London International Financial Futures Exchange (now Euronext.liffe) in 1982, Deutsche Terminbörse (now Eurex), and the Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM). Today, there are over 90 futures and futures options exchanges globally, including:

- CME Group (CBOT and CME) – Currencies, Various Interest Rate Derivatives (including US Bonds); Agriculture (Corn, Soybeans, Soy Products, Wheat, Pork, Cattle, Butter, Milk); Indices (Dow Jones Industrial Average, NASDAQ Composite, S&P 500, etc.); Metals (Gold, Silver).

- NYMEX (CME Group) – Energy and metals: crude oil, gasoline, heating oil, natural gas, coal, propane, gold, silver, platinum, copper, aluminum, and palladium.

- Dubai Mercantile Exchange (DME) – Notably Oman Crude, Dubai Platts, and Singapore Fuel Oil.

- Intercontinental Exchange (ICE Futures Europe) – Formerly the International Petroleum Exchange, trading energy products including crude oil, heating oil, gas oil (diesel), refined petroleum products, electric power, coal, natural gas, and emissions.

- NYSE Euronext – Absorbed Euronext, including LIFFE (which merged with the London Commodities Exchange (LCE) in 1996) – Softs: grains and meats. Also includes index futures like EURIBOR, FTSE 100, CAC 40, AEX index.

- Eurex – Part of Deutsche Börse, also operates the Swiss Options and Financial Futures Exchange (SOFFEX) and the European Energy Exchange (EEX).

- South African Futures Exchange (SAFEX)

- Sydney Futures Exchange

- Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM)

- Tokyo Financial Exchange (TFX) – Euroyen Futures, Overnight Call Rate Futures, SpotNext Repo Rate Futures

- Osaka Exchange (OSE) – JGB Futures, TOPIX Futures, Nikkei Futures, RNP Futures

- London Metal Exchange – Metals: copper, aluminum, lead, zinc, nickel, tin, and steel

- Intercontinental Exchange (ICE Futures U.S.) – Formerly New York Board of Trade – Softs: cocoa, coffee, cotton, orange juice, sugar

- JFX Jakarta Futures Exchange

- Montreal Exchange (MX) – Known in French as Bourse De Montreal: Interest Rate and Cash Derivatives including Canadian 90 Days Bankers’ Acceptance Futures, Canadian government bond futures, S&P/TSX 60 Index Futures, and other Index Futures

- Korea Exchange (KRX)

- Singapore Exchange (SGX) – Merged with Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX)

- ROFEX – Rosario (Argentina) Futures Exchange

- NCDEX – National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange, India

- National Stock Exchange of India – The largest derivatives exchange by contract volume

- EverMarkets Exchange (EMX) – Planned for launch in late 2018, focusing on global currencies, equities, commodities, and cryptocurrencies

- FEX Global – Financial and Energy Exchange of Australia

- Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE) – Mainly agricultural and industrial products

- Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE) – Primarily serves metal and foodstuff markets

- Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange (ZCE) – Focused on agricultural products and petrochemicals

- China Financial Futures Exchange (CFFEX) – Specializes in index futures and currencies

Codes

Futures contract codes typically consist of five characters. The first two characters denote the contract type, the third character indicates the month, and the last two characters represent the year.

On CME Group markets, the third character for month codes is as follows:

- January = F

- February = G

- March = H

- April = J

- May = K

- June = M

- July = N

- August = Q

- September = U

- October = V

- November = X

- December = Z

For example, CLX14 represents a Crude Oil (CL) contract expiring in November (X) 2014 (14).

Futures Contract Users

Futures traders generally fall into two categories: hedgers and speculators. Hedgers are those with an interest in the underlying asset (which could include intangible assets like an index or interest rate) seeking to mitigate the risk of price fluctuations. Speculators, on the other hand, aim to profit by predicting market movements and entering into derivative contracts related to the asset, often without any intention of taking or making delivery of the underlying asset. In essence, speculators seek to gain exposure to the asset through long futures contracts or benefit from falling prices via short futures contracts.

Hedgers

Hedgers often include producers and consumers of commodities or holders of assets affected by variables such as interest rates. For instance, farmers may sell futures contracts on their crops or livestock to lock in a price and facilitate planning. Similarly, livestock producers might purchase futures to manage feed costs. In financial markets, creators of interest rate swaps or equity derivatives use futures or index futures to manage or eliminate risk.

It is crucial for those buying or selling commodity futures to exercise caution. If a company hedges against price increases but the market price turns out to be significantly lower at delivery, it could face severe competitiveness issues.

Investment fund managers can use financial asset futures to handle portfolio interest rate risk or duration without making direct cash transactions through bond futures. Firms that receive capital inflows or calls in a currency different from their base currency might use currency futures to hedge future currency risk.

Speculators

Speculators are typically classified into three categories: position traders, day traders, and swing traders, though many variations and unique styles exist. With an increasing number of investors entering the futures markets, there has been debate about whether speculators contribute to heightened volatility in commodities like oil. Experts remain divided on this issue.

An example involving both hedging and speculation is a mutual fund or managed account aiming to track the performance of a stock index like the S&P 500. The portfolio manager might “equitize” any unintended cash holdings by investing in S&P 500 stock index futures, thus aligning the portfolio with the index without immediately purchasing the individual stocks. This approach preserves diversification and maintains a higher proportion of assets in the market, helping reduce tracking error. When feasible, the manager can close the futures contract and purchase the individual stocks.

The primary social benefit of futures markets is in risk transfer and increased liquidity, allowing traders with different risk and time preferences to exchange risk efficiently.

Options on Futures

Options on futures, sometimes known simply as “futures options,” include put options (the right to sell a futures contract) and call options (the right to buy a futures contract). For both types, the option strike price is the specified futures price at which the futures contract is traded if the option is exercised. Futures are often used because they are delta one instruments. Options on futures are priced similarly to options on traded assets, typically using an extension of the Black-Scholes formula known as the Black model. Options on futures may be referred to as “futions” since they behave like options but settle like futures.

Investors can take on the role of either option seller (or “writer”) or option buyer. Sellers typically face more risk as they are obligated to assume the opposite futures position if the option is exercised. The price of an option is driven by supply and demand and includes the option premium, which is the cost paid to the option seller for offering the option and assuming risk.

While futures generally expire on a quarterly or monthly basis, their options may expire more frequently, such as daily. Examples include options on futures with underlying assets like gold (XAU), stock indexes (Nasdaq, S&P 500), or commodities (oil, VIX). Stock exchanges and clearing houses provide information on these products (CME, COMEX, NYMEX).

Futures contracts users

Traditionally, futures market participants are categorized into two primary camps: hedgers and speculators. Hedgers have a vested interest in the asset that underlies the futures contract, which may be a tangible commodity or an abstract concept like an index or a rate. Their goal is to mitigate the risk associated with price fluctuations. On the other hand, speculators aim to profit from their predictions of market trends by entering into derivative contracts that reference the asset, purely for the purpose of trading rather than for the actual possession or delivery of the asset itself. Essentially, speculators are looking to gain exposure to the asset through long futures positions or to counteract such exposure via short futures positions.

Hedgers

Entities engaged in the production or consumption of commodities, or those holding assets vulnerable to fluctuations such as interest rates, often employ hedging strategies.

In the realm of agricultural markets, it is common for farmers to enter into futures contracts for their agricultural produce and livestock to secure a predetermined price, facilitating better planning. Livestock breeders also utilize futures contracts to hedge against the cost of feed, ensuring a predictable expense for this essential input. In the contemporary financial sector, creators of interest rate swaps or equity derivatives utilize financial and equity index futures as a means to mitigate or eliminate the associated risks.

Prudence is essential for those participating in commodity futures markets. A company that hedges against rising commodity prices by purchasing futures contracts may face severe competitive disadvantages if the market price at the time of delivery is significantly lower, as exemplified by the case of VeraSun Energy.

Portfolio managers and sponsors of investment funds can utilize futures on financial assets to regulate the interest rate risk or duration of their portfolios, circumventing the need for direct cash transactions through bond futures. Additionally, investment firms that encounter capital inflows in currencies different from their base currency can mitigate the currency risk associated with these inflows by employing currency futures.

Speculators

Speculators are generally categorized into three main groups: long-term position traders, short-term day traders, and intermediate-term swing traders, with many investors adopting hybrid or unique approaches. The influx of investors into futures markets has sparked debates in recent years regarding the potential impact of speculators on the volatility of commodities such as oil, with opinions among experts being quite varied.

A scenario that encompasses both hedging and speculative elements involves a mutual fund or an independently managed account that aims to mirror the performance of a stock index, like the S&P 500. The portfolio manager often utilizes S&P 500 stock index futures to efficiently and economically convert unexpected cash positions or inflows into equity. This strategy provides the portfolio with exposure to the index, aligning with the investment goal of the fund or account, without the immediate need to purchase a proportional share of each of the 500 constituent stocks. It also ensures a balanced diversification, maintains a higher investment rate in the market, and minimizes the tracking discrepancy in the performance of the fund or account. When it becomes economically viable—meaning an optimal number of shares for each position within the fund or account can be acquired—the portfolio manager can then close the futures contract and proceed to buy individual stocks.

The societal benefit of futures markets is primarily seen in the redistribution of risk and the enhanced liquidity that facilitates transactions between parties with divergent risk appetites and time horizons, such as from a hedger to a speculator.

Options on futures

Trading Options on Futures

Options can frequently be found in the futures market, which are sometimes referred to as “futures options.” A put option confers the right to sell a futures contract, while a call option grants the right to purchase one. In both instances, the strike price of the option is the predetermined price at which the futures contract is executed if the option is activated. Futures are commonly utilized due to their characteristic of having a unit delta. Pricing for futures options can be approached similarly to that of options on other tradable assets, employing an adaptation of the Black-Scholes model known as the Black model.

For options on futures, where the premium is paid only upon the contract’s termination, the positions are often termed “futons,” as they function similarly to options but are settled in the manner of futures.

Investors have the choice to assume the role of either the option seller, also known as the “writer,” or the option buyer. Option writers are typically perceived as bearing greater risk, as they are legally bound to assume the opposing futures position if the option buyer decides to exercise their option rights. The cost of an option is influenced by market forces and includes the option premium, which is the fee paid to the option writer for providing the option and accepting the associated risk.

Unlike futures, which typically have a quarterly or monthly expiration, options on futures expire more frequently, such as on a daily basis. Examples include options on futures with underlying assets like gold (XAU), indices (Nasdaq, S&P 500), or commodities (oil, VIX). Financial exchanges and their clearing institutions offer comprehensive information on these financial instruments (CME, COMEX, NYMEX).

Futures contract regulations

In the United States, all futures transactions are overseen by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which is an independent agency of the federal government. The CFTC has the authority to impose fines and other penalties on individuals or companies that violate regulations. While the CFTC oversees all transactions by law, individual exchanges may also have their own rules and can impose additional fines or extend those issued by the CFTC.

The CFTC releases weekly reports detailing the open interest of market participants for each market segment that has more than 20 participants. These reports, known as the ‘Commitments of Traders Report’, COT-Report, or simply COTR, are published every Friday and include data from the previous Tuesday. They provide information on open interest, distinguishing between reportable and non-reportable open interest, as well as commercial and non-commercial open interest.

Definition of a futures contract

According to Björk, a futures contract for the delivery of item J at time T is defined as follows:

At time t, there is a market-quoted price F(t,T) for the delivery of J at time T, referred to as the futures price. The cost to enter into a futures contract is zero.

Throughout any interval ([t,s]), the holder of the contract will receive an amount equal to (F(s,T) – F(t,T)), which reflects the instantaneous marking to market.

At the contract’s maturity, time T, the holder pays (F(T,T)) and receives J. It is important to note that (F(T,T)) should be equivalent to the spot price of J at time T.

Futures versus forwards

A forward contract shares similarities with a futures contract in that both outline the agreement to exchange goods at a predetermined price on a future date. However, unlike futures, forwards are not traded on a formal exchange, and therefore, do not involve periodic payments due to the process of marking to market.

While both futures and forward contracts entail the delivery of an asset at a set price on a future date, they differ in key aspects:

- Futures are traded on an exchange, whereas forwards are private transactions conducted over-the-counter (OTC).

This means that futures are standardized and regulated by the exchange, while forwards are tailored to the needs of the parties involved and are not subject to exchange oversight. - Futures require margin accounts, whereas forwards do not.

This accounts for the lower credit risk associated with futures, as the margin system and daily price adjustments minimize financial exposure. Forwards, lacking this mechanism, carry a higher credit risk.

The Futures Industry Association (FIA) has reported that in 2007, the volume of futures contracts traded reached 6.97 billion, marking a 32% increase from the previous year.

Exchange vs. OTC Trading

Futures contracts are exclusively traded on a centralized exchange, while forward contracts are transacted directly between two parties in an OTC setting. This leads to:

- A high degree of standardization in futures due to their exchange-traded nature, contrasting with the customizable nature of forwards in an OTC environment.

- In the event of physical delivery, a forward contract specifies the delivery counterparty, whereas in futures, the clearing house assigns the counterparty.

Exchange for Related Positions

Various trading strategies have emerged that involve the exchange of a futures contract for an OTC position, a physical commodity, or a cash asset that aligns with certain criteria such as size and correlation to the underlying commodity risk.

Margining

Further details on margining can be found in the finance section on margin. Futures contracts are adjusted daily to reflect the current spot price of a forward with the same delivery price and underlying asset, based on mark to market.

Forwards, on the other hand, do not adhere to a daily margining standard. Parties involved in a forward agreement may agree to settle differences periodically, such as quarterly. The absence of daily margining in forwards can result in a significant divergence between the delivery price and the market price due to asset price fluctuations, leading to an accumulation of unrealized gains or losses.

Futures contracts are ‘trued-up’ daily by comparing the market value of the futures to the collateral securing the contract, ensuring alignment with brokerage margin requirements. This process involves the party incurring a loss providing additional collateral to cover the shortfall.

In contrast, forwards do not have regular true-ups, which means that the unrealized gains or losses accumulate and only become realized at the time of delivery or contract closure. This results in a higher credit risk for forwards compared to futures, and differences in how funding is charged.

The lack of daily margin adjustments in forwards introduces credit risk, which is mitigated in futures by the daily updates to the price of an equivalent forward purchased on that day. This reduces the amount of additional funds required to settle the futures contract on the final day to just the day’s gain or loss.

Moreover, the risk of settlement failure in futures is borne by the exchange rather than an individual party, further reducing credit risk in futures trading.

Example: Imagine a futures contract with a delivery price of $100. Suppose on day 50, the same contract costs $88, and on day 51, it’s priced at $90. The mark-to-market process would require the holder of the contract to pay $2 on day 51 to reflect the change in the forward price. This payment is transferred through margin accounts to the other party.

A forward contract holder, in contrast, may not make any payments until the final settlement day, potentially accumulating a significant balance, which may be accounted for by considering credit risk. Aside from minor convexity bias effects, the total loss or gain from futures and forwards with equal delivery prices is the same, but futures holders experience this incrementally on a daily basis, tracking the forward’s daily price changes, while the forward’s spot price converges to the settlement price at expiry. Thus, under mark to market accounting, the gain or loss accrues over the holding period for both assets; for futures, this is realized daily, while for forwards, it remains unrealized until the contract’s expiration.

In exchange-traded futures, the clearing house acts as an intermediary for every trade, eliminating the risk of counterparty default. The only remaining risk is the unlikely event of the clearing house defaulting.

Leave a Reply