A currency is a system of money, in any form, used as a medium of exchange, including items like banknotes and coins. [1][2]Broadly speaking, currency refers to a standardized monetary system that is widely accepted within a specific context or country over time.[3] Examples of such systems include the British Pound (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$), which are all examples of government-backed fiat currencies[4].Currencies serve as stores of value and are traded internationally in foreign exchange markets, which establish their comparative values. These currencies may be either selected by individuals or mandated by governments, each having its own scope of acceptance; for example, legal tender laws may stipulate the use of a specific currency for payments to governmental bodies.

The term “currency” also appears in related contexts such as banknotes, coins, and money. This discussion focuses on the currency systems of different nations.

Currencies can be categorized into three main monetary systems: fiat money, commodity money, and representative money, based on what underpins their value (whether it’s the broader economy or government-held precious metals). Certain currencies are recognized as legal tender in specific regions or for particular transactions, such as tax payments or fees to government agencies. Others are traded primarily for their intrinsic economic value.

In recent years, the idea of digital currency has gained traction. It remains uncertain whether government-issued digital currencies (like China’s digital renminbi) will be successfully developed and implemented.[5] On the other hand, digital currencies not issued by governments, such as cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, differ because their value relies on market dynamics without any inherent safety measures. Various nations have raised concerns about the potential for cryptocurrencies to facilitate illegal activities, including fraud, ransomware attacks, money laundering, and terrorism.[6] In 2014, the U.S. IRS classified virtual currency as property for federal income tax purposes and illustrated how traditional tax principles applicable to property transactions extend to virtual currencies.[7]

History

Early currency

Initially, currency served as a form of receipt, denoting the storage of grain in temple granaries in ancient Sumer, Mesopotamia, and Egypt.

In this early phase of currency, metals were utilized to symbolize the value of commodities stored. This system supported trade in the Fertile Crescent for over 1500 years. However, the collapse of Near Eastern trade systems exposed a critical issue: in times when secure storage of value was lacking, the reliability of a currency depended on the strength of the defenses protecting it. The reach of trade was directly linked to the credibility of military forces. By the late Bronze Age, treaties had secured safe routes for merchants across the Eastern Mediterranean, from Minoan Crete and Mycenae in the northwest to Elam and Bahrain in the southeast. Although the exact currency used in these transactions is unclear, copper ingots shaped like oxhides, produced in Cyprus, are thought to have played a role.

The decline in trade associated with the Bronze Age collapse, potentially due to the incursions of the Peoples of the Sea, ended the use of oxhide-shaped ingots. It wasn’t until the revival of Phoenician trade in the 10th and 9th centuries BC that prosperity returned and true coinage emerged, likely beginning with Croesus of Lydia in Anatolia and later spreading to Greece and Persia. In Africa, various forms of value storage have been used, such as beads, ingots, ivory, weaponry, livestock, manilla rings, shell money, and ochre. From the 15th century onward, manilla rings in West Africa were used as currency in the slave trade. African currency remains diverse, with various barter systems still prevalent in many regions.

Coinage

The widespread use of metal coins led to the metals themselves becoming the primary store of value. Initially, this involved copper, but over time, silver and gold also became standard, with bronze occasionally used. Nowadays, various non-precious metals are also utilized for minting coins. Metals were extracted, weighed, and stamped into coins to ensure that their value was based on a known quantity of the precious metal. While counterfeiting was a concern, the standardization of coins introduced a new unit of account, paving the way for the development of banking. Archimedes’ principle further advanced this system by allowing the precise measurement of a coin’s metal content, thus enabling the detection of tampered or debased coins (see Numismatics).

Major economies that used coinage typically had a range of coins with different values, made from copper, silver, and gold. Gold coins, being the most valuable, were used for significant transactions, military payments, and state expenditures. Their value often served as a benchmark for units of account. Silver coins facilitated medium-sized transactions and sometimes served as units of account as well. Copper or mixed-metal coins were commonly used for everyday purchases. This tiered system was also evident in ancient India during the era of the Mahajanapadas. The relative value of these metals varied significantly depending on the time and place; for example, the influx of silver from the Harz mountains in central Europe or from the New World after Spanish conquests reduced its value. Despite these fluctuations, gold consistently remained more valuable than silver, and silver more valuable than copper.

Paper money

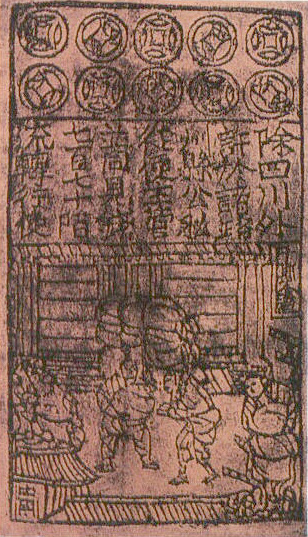

In premodern China, the need to simplify transactions and reduce the burden of handling large quantities of copper coins led to the development of paper money, or banknotes. This transition began in the late Tang dynasty (618–907) and continued through the Song dynasty (960–1279). Initially, merchants used paper notes as receipts for deposits, which were issued by wholesalers and were valid only within specific regions. By the 10th century, the Song dynasty began issuing these notes within its state-controlled salt trade. In the early 12th century, the government took over the issuance of these notes, but they remained valid only locally until the mid-13th century, when standardized government-issued paper money became widely accepted across the country. The advent of woodblock printing and, later, Bi Sheng’s movable type printing technology in the 11th century facilitated the mass production of these notes.

During the same period, the medieval Islamic world saw the creation of a robust monetary system, fueled by the widespread use of the stable dinar currency. Innovations by Muslim economists, traders, and merchants introduced early forms of credit[8], cheques, promissory notes[9], savings accounts, transaction accounts, loans, trusts, exchange rates, credit and debt transfers, and banking institutions[10].

In Europe, Sweden was the first to regularly issue paper currency in 1661, although Washington Irving notes an earlier instance of its emergency use by the Spanish during the Conquest of Granada. Sweden’s abundant copper led to the circulation of large, heavy copper coins, making paper currency an attractive alternative.

Paper money offered several benefits: it reduced the need to transport valuable gold and silver, facilitated the lending of gold or silver without actually moving the physical metal, and allowed currency to be divided into credit and specie-backed forms. It also enabled investment in joint-stock companies and the redemption of shares in paper form.

However, paper currency also had drawbacks. It lacked intrinsic value, which meant that issuing authorities could print more notes than they had precious metals to back them. This practice could lead to inflation, a phenomenon noted by David Hume in the 18th century. Excessive issuance of paper money often resulted in inflationary bubbles that could burst if there was a rush to redeem notes for hard currency. Additionally, the association of paper money with wartime financing and standing armies led to skepticism and hostility towards it in Europe and America. Despite this, paper currency became an integral part of financial systems, with major nations establishing mints for coins and branches of their treasuries to manage taxation and precious metal reserves.

By the 19th century, both silver and gold were considered legal tender, though their exchange rates fluctuated due to increased supply and trade. This led to the concept of bimetallism, where both metals backed the currency. Governments began using paper money as a policy tool, such as the United States greenback for military expenses, and controlled the terms of note redemption.

By 1900, most industrialized nations had adopted some form of gold standard, with paper notes and silver coins in circulation. According to Gresham’s law, gold and silver were hoarded while paper money was used for transactions. This shift occurred unevenly, often during times of war or financial crisis, and continued until the late 20th century, when the regime of floating fiat currencies replaced the gold standard. The United States abandoned the gold standard in 1971 in what is known as the Nixon shock, and no country now maintains an enforceable gold or silver standard.

Banknote era

A banknote, also known as a bill, is a form of currency widely accepted as legal tender in numerous countries. Along with coins, banknotes represent the cash component of a currency system. Originally, banknotes were primarily made from paper. However, in the 1980s, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation pioneered the use of polymer for currency, which began circulation in 1988 to mark the country’s bicentenary[11]. Polymer banknotes had been introduced earlier in 1983 in the Isle of Man. By 2016, polymer banknotes were in use in over 20 countries (or more than 40 if including commemorative issues)[12], offering extended durability and enhanced resistance to counterfeiting.

Modern currencies

The currency in use is determined by the principle of lex monetae, which means that each sovereign state has the authority to choose its own currency. (See Fiat currency.)

Currency codes and currency symbols

In 1978, the International Organization for Standardization introduced a system of three-letter codes (ISO 4217) to represent different currencies. This system assigns two letters to identify a country and a third letter to specify the particular currency unit[13].

Various currencies also use symbols to represent them. However, these symbols lack international standardization and can be used for multiple currencies; for example, the dollar sign is employed by several different currencies.

Alternative currencies

Unlike government-issued currencies that are centrally controlled, alternative currencies operate within decentralized networks that are not managed by any central authority. Examples of these include cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum’s ether, which rely on cryptographic methods for transaction validation, with each transaction verified by users across the network. Typically, these cryptocurrencies are not backed by tangible assets. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has classified Bitcoin (and similar assets) as commodities under the Commodity Exchange Act.

There are also branded currencies, such as those used for loyalty programs or store credits, which operate within specific commercial contexts. Examples include BarterCard, various loyalty points systems (like those used by credit cards or airlines), and in-game currencies from online games, all of which are tied to the reputation and usage within particular markets.[15]

Historically, pseudo-currencies have included forms like company scrip, which could only be spent at company-owned stores. Modern equivalents, such as the tokens used in local exchange trading systems (LETS), function as barter systems rather than traditional currencies.

Some alternative currencies are entirely digital and internet-based. For instance, Bitcoin[16] operates independently of any national currency, while the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) are based on a basket of various currencies and assets.

Governments often restrict or ban the use of alternative currencies to maintain the legitimacy and stability of their official currency. In the United States, Article I, Section 8, Clause 5 of the Constitution grants Congress the authority to coin money and regulate its value. This provision ensures a uniform standard of value and a singular monetary system for all transactions. To protect this system, federal law prohibits individuals or entities from creating private currencies that compete with the official U.S. money supply.[17]

Control and production

Typically, a central bank has the sole authority to issue all forms of legal currency, including coins and banknotes, and to regulate the circulation of alternative currencies within its jurisdiction, whether that’s a single country or a group of countries. This authority includes overseeing the production of currency by commercial banks through monetary policy measures.

An exchange rate represents the value at which one currency can be traded for another. This rate is essential for trade between different currency zones. Exchange rates can be either floating or fixed. Floating rates are influenced by market forces on a daily basis, while fixed rates are maintained by governmental interventions, where authorities buy or sell their currency to keep the rate steady.

When a country manages its own currency, control is typically exercised either by a central bank or a Ministry of Finance, collectively known as the monetary authority. This body oversees monetary policy and can have varying levels of independence from its governing government, depending on how it was established.

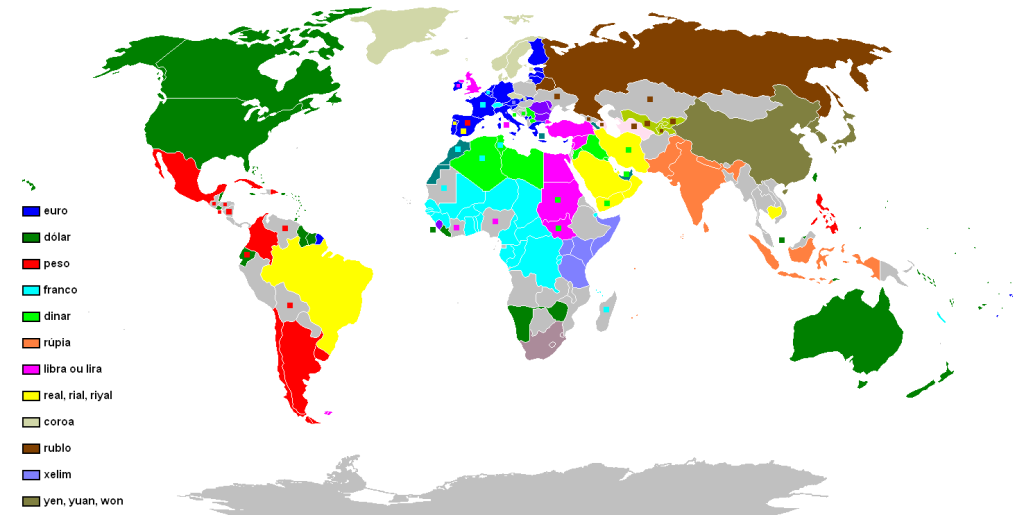

Different countries can share the same currency name, such as the dollar used in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Conversely, multiple countries can adopt a single currency, like the euro or the CFA franc. In some cases, a country may accept the currency of another nation as legal tender. For instance, Panama and El Salvador use the US dollar, and from 1791 to 1857, the Spanish dollar was legal tender in the United States. Some countries have used currency boards or re-stamped foreign coins, as seen with Ecuador’s current system.

Currencies usually have a primary unit and a fractional unit, typically 1/100 of the main unit, such as 100 cents to a dollar or 100 pence to a pound. However, some currencies, like the Icelandic króna and the Japanese yen, do not have fractional units.

Mauritania and Madagascar are unique in that they have theoretical fractional units not based on the decimal system: the Mauritanian ouguiya is divided into 5 khoums, and the Malagasy ariary into 5 iraimbilanja. Historically, these units were linked to weights of gold but have become largely obsolete due to inflation.[18]

Currency convertibility

Currency convertibility varies globally, with the possibility of converting local currency to another or vice versa being influenced by central bank or government regulations. These conversions occur in the foreign exchange market and are categorized based on their level of restriction:

Fully Convertible

Currencies with no restrictions on the amount that can be traded internationally and where the government does not impose a fixed or minimum value on the currency. The US dollar is a prominent example of a fully convertible currency.

Partially Convertible

Currencies subject to central bank controls over international investments. While domestic transactions are generally unrestricted, converting these currencies for international use often requires special permissions. The Indian rupee and the renminbi are examples of partially convertible currencies.

Nonconvertible

Currencies that are neither traded internationally nor permitted for conversion by individuals or businesses. These currencies are sometimes referred to as blocked currencies. Examples include the North Korean won and the Cuban peso.

The exchange rate between different currencies is influenced by three main factors: trade in goods and services, capital flows, and national policies.

Trade in Goods and Services

The flow of goods and services, including those like tourism, hospitality, and advertising, impacts the cost and price of international trade. This can indirectly influence exchange rates. For instance, a high volume of international tourism and foreign students can affect the supply and demand for local goods and services, which in turn influences the exchange rate. The global competitiveness of goods and services also plays a role in shaping exchange rate movements.

Capital Flows

National currencies are traded internationally for investment purposes, with investment opportunities attracting foreign capital. This influx of foreign currencies becomes part of central bank reserves. Currency exchange rates are influenced by continuous trading in foreign exchange markets, where currencies are bought and sold by individuals, banks, and investment firms. Interest rate changes, fluctuations in capital markets, and shifts in investment opportunities all affect global capital flows and, consequently, exchange rates.

National Policies

A country’s foreign trade, monetary, and fiscal policies impact exchange rate fluctuations. Trade policies, such as tariffs and import standards, affect commodity prices and export competitiveness. Monetary policy influences the money supply and interest rates, directly affecting exchange rates. Fiscal policies, including taxation and government spending, influence economic performance and capital returns, impacting national debt and credit ratings. These policies shape the relationship between domestic and foreign currencies, thus affecting exchange rates.

Currency convertibility is essential for economic development and financial integration. Achieving full currency convertibility involves meeting specific conditions:

Robust Microeconomic Environment

A competitive domestic market is crucial for effective currency convertibility. Firms need to compete with international counterparts, which affects the overall success of currency convertibility. A sound microeconomic environment supports a stable macroeconomic foundation.

Stable Macroeconomic Conditions

Currency convertibility requires a stable economy, free from severe inflation and overheating. The government must manage the economy with appropriate macroeconomic policies to mitigate the impact of currency fluctuations.

Open and Balanced Economy

A sustainable international balance of payments reflects a well-structured economy. Currency convertibility can challenge this balance and the government’s control over international transactions. Adequate international reserves are necessary to address foreign exchange shortages.

Appropriate Exchange Rate Regime

Maintaining an appropriate exchange rate is crucial for stability before and after achieving currency convertibility. An exchange rate that is too high or too low can lead to market speculation and disrupt economic stability. Therefore, a suitable exchange rate regime is essential for managing stability.

Local currency

In economics, a local currency refers to a type of currency that operates independently of national government backing and is used within a specific, limited area. Proponents like Jane Jacobs suggest that such currencies can help economically struggling regions by providing a medium of exchange for local services and goods, which can stimulate regional economic activity. This concept reflects the original role of money as a facilitator of trade. However, critics argue that local currencies can disrupt economies of scale and comparative advantage and might even be used for tax evasion.

Local currencies may also emerge during periods of national economic instability. For instance, during the Argentine economic crisis of 2002, local governments issued IOUs that began to function like local currencies.

A notable example of a local currency is the LETS (Local Exchange Trading System) introduced on Vancouver Island in the early 1980s. In response to high lending rates—reaching 14% from the Canadian Central Bank and up to 19% from chartered banks—the local community established their own currency to counteract the shortage of credit and currency.[20]

References

- ^ “Currency”. The Free Dictionary.

currency […] 1. Money in any form when in actual use as a medium of exchange, especially circulating paper money.

2. ^ Bernstein, Peter (2008) [1965]. “4–5”. A Primer on Money, Banking and Gold (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-28758-3. OCLC 233484849.

3. “Currency”. Investopedia.

4. “Guide to the Financial Markets” (PDF). The Economist. p. 14. Determining the relative values of different currencies is the role of the foreign-exchange markets.

5. “Electronic finance: a new perspective and challenges” (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. November 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

6. “Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World”. Library of Congress. August 16, 2019. p. 1. One of the most common actions identified across the surveyed jurisdictions is government-issued notices about the pitfalls of investing in the cryptocurrency markets. […] Many of the warnings issued by various countries also note the opportunities that cryptocurrencies create for illegal activities, such as money laundering and terrorism.

7. “Frequently Asked Questions on Virtual Currency Transactions”. December 31, 2019.

8. Banaji, Jairus (2007). “Islam, the Mediterranean and the Rise of Capitalism”. Historical Materialism. 15 (1): 47–74. doi:10.1163/156920607X171591. ISSN 1465-4466. OCLC 440360743. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

9. Lopez, Robert Sabatino; Raymond, Irving Woodworth; Constable, Olivia Remie (2001) [1955]. Medieval trade in the Mediterranean world: Illustrative documents. Records of Western civilization.; Records of civilization, sources and studies, no. 52. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12357-0. OCLC 466877309. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012.

10. Labib, Subhi Y. (March 1969). “Capitalism in Medieval Islam”. The Journal of Economic History. 29 (1): 79–86. doi:10.1017/S0022050700097837. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2115499. OCLC 478662641. S2CID 153962294.

11. “History of Banknotes”. Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

12. Wang, Ping (June 2016). “The Future Is Plastic – Currency Notes”. Finance & Development. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

13. “ISO 4217 – Currency Codes”. International Organisation for Standardisation. 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2022. The alphabetic code is based on another ISO standard, ISO 3166, which lists the codes for country names. The first two letters of the ISO 4217 three-letter code are the same as the code for the country name, and, where possible, the third letter corresponds to the first letter of the currency name.

14. “Bitcoin Basics” (PDF). Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

15. “10 alternative currencies, from Bitcoin to BerkShares to sweat to laundry detergent”. TED (conference). July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013.

16. Hough, Jack (June 3, 2011). “The Currency That’s Up 200,000 Percent”. SmartMoney (The Wall Street Journal). Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

17. “Defendant Convicted of Minting His Own Currency”. FBI. March 18, 2011.

18. Turk, James; Rubino, John (2007) [2004]. The collapse of the dollar and how to profit from it: Make a fortune by investing in gold and other hard assets (Paperback ed.). New York: Doubleday. pp. 43 of 252. ISBN 978-0-385-51224-4. OCLC 192055959.

19. Linton, Michael; Bober, Jordan (November 7, 2012). “Opening Money”. The Extraenvironmentalist (Interview). Interviewed by Seth Moser-Katz; Justin Ritchie. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

20. “Opening Money” (MP3). The Extraenvironmentalist (Podcast). Retrieved December 29, 2016.[19]

Leave a Reply